By Edward Guthmann

SAN FRANCISCO -- Mike Kuchar swears he remembers being born. Not his own birth, exactly, but the arrival of his twin brother, George, minutes later.

"I can't get it out of my mind," he says. "I remember seeing him being slapped. And the weirdest thing about it is, I remember thinking, 'I hope he's going to cry the first time. Otherwise they'll hit him again.' "

The Kuchars are the Bronx-born film mavericks who gave the world such underground gems as "Hold Me While I'm Naked," "Confessions of a Teenage Rumpot" and "Sins of the Fleshapoids." Cheerfully dogged in their pursuit of an artistry that bypassed commerce and trends, the Kuchars are bona fide filmmaking heroes.

In September, six days after his 69th birthday, George Kuchar died of prostate cancer. It was a huge jolt to the Bay Area film community, which treasured George for his talent as well as his generosity and droll humor, and a devastating blow to his significantly shyer, quieter twin.

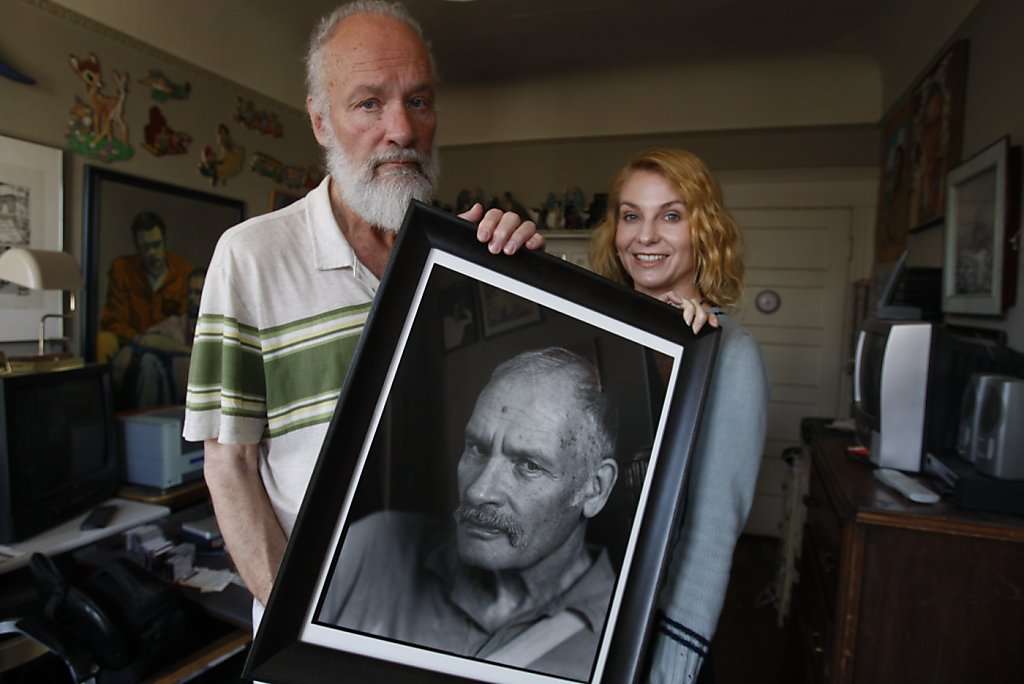

Mike, who shared the same Mission District apartment with his brother for 31 years, and who once said, "We're actually like one person, but we're split in two" - is left. His mother died in 2007, his father decades earlier. In April, Tippi, the family cat that George and Mike adored, passed away.

"It's like being on an island," he says. "Everything you knew, little by little, starts to disappear. The water's just getting higher and higher. And you find you're the lone survivor.

Some days are OK. "I'm functioning, let's put it that way," Mike says during a long interview in his apartment. "What I do is, I keep busy on projects. That's the glue that holds me together. Otherwise it's just real depressing."

'He's not lying down'

Shortly before George's death, Mike was asked by the San Francisco Art Institute to take over the film-production class that George had taught since the early '70s. He recently completely two semesters - casting, assembling props and equipment, filming, editing - and he'll continue teaching in the fall.

"He is living his life, and he's not lying down," says Eric Smith, a filmmaker and clothing designer who was close to the Kuchars and became an important caregiver in George's last months. "One of the last things George said to him was, 'Carry on.' That's kind of his mantra. He's holding the torch."

Smith is one of the curators of "Mike's Men: Sex, Guys and Videotape!," a solo exhibition of Mike's drawings and video. A collection of erotic drawings made for underground gay comics from the late 1970s to mid-2000s, "Mike's Men" opens June 1 at Magnet ( www.magnetsf.org), 4122 18th St. in the Castro district.

"Hopefully, it'll give Mike some visibility, maybe some financial benefit," Smith says. "I really love Mike, and I wanted to do it for him." His drawings are also on display through August at the Apartment, a gallery in Vancouver, British Columbia, and will be included in the Frieze Art Fair in London in October.

Another friend who's remained close to Mike is Jennifer Kroot, director of the 2009 biographical documentary "It Came From Kuchar." In the months since George's death, she says, Mike has been less reclusive. "For whatever reason, he's feeling a little more open to having a few more people in his life.

"They say if you have two pets," Kroot adds, "and one of them dies before the other, the remaining cat or dog takes on some traits of the one that has passed. ... I feel like Mike has taken on a little bit of George, which maybe is even easier if you're a twin."

Ironically, the loss of his brother created a modest financial gain for Mike. He has the San Francisco Art Institute salary, and he receives money from George's estate.

Not used to money

Having money is a novelty for Mike Kuchar. Until his mother's death in 2007 he spent eight months a year living with her in the Bronx apartment - in part because she needed care, in part because he couldn't support himself on his film projectionist's salary.

To indulge himself, he's been decorating. The apartment, a kitschy, chaotic mash of Miss Havisham and "Wayne's World," is blooming now with Roman and Grecian statuary, swords and helmets that he buys from high-end catalogs.

"I have more money," he says, "but I find that I'd rather have my brother."

Speaking with Mike Kuchar can be an odd experience. He makes very little eye contact, and he speaks in fragments rather than complete sentences. He seems overwhelmed, a bit haunted by the business of being alive. And yet there's a sweetness and vulnerability to him - qualities that everyone contacted for this article mentioned.

"I always thought Mike was even more eccentric than George in some ways," says John Waters, a longtime friend who credits the Kuchars with inspiring his own film career. "I mean that as a compliment. He's a true Beatnik elder statesman."

Only a twin knows

No one but a twin can understand the intricate, intimate nature of that relationship. For the Kuchars, who had no other siblings and lived together most of their 69 years, the bond is especially strong. They started making films together at age 12, and although their mother was a source of love, their philandering father never understood his sons' obsessions and campy, absurdist humor.

"He knew we were strange," Mike says. "He was a truck driver, very macho. He smoked three packs of Camels every day. The house was like an acid fog. And he would come home and see us watching the Liberace show on TV. He couldn't understand that.

"I felt sorry for him. I couldn't be a baseball player, or go out for beers with him. I just wasn't that kind of a person."

Having a common adversary probably made the twins closer. So did their passion for filmmaking. And, although sexuality was something neither discussed freely - choosing instead to work it out in their films - the fact that both brothers were gay was another important factor.

Today, Mike says there were never serious fights between them. Even though George's films were more celebrated, there were just "slight tinges of jealousy." Never an estrangement.

"We were always together. We always understood each other. We had our own lives: As twins you maintain a certain equilibrium: like, he's got his life and I've got mine. But it's family. It's family, and it always was."

When George first learned of his cancer diagnosis a year and a half before his death, he kept it a secret from all but two or three people. When he was no longer able to walk last summer, he entered Coming Home Hospice in the Castro district.

George's room was filled with a constant stream of friends and well-wishers, and the atmosphere was often celebratory with George holding court and making his visitors laugh. "He was very appreciative of the people who visited," Mike says. But "I knew that this was serious.

"Occasionally I'd say, 'Are you tired? Are you tired of being presentable?' And most of the times, no, he wasn't. But then he was pretty stern and he would speak up and say, 'Look, I need some time with my brother.' And in a gentle way."

A magical wish

In his last weeks, Mike says, George had a magical wish - to relocate, despite his illness and infirmity, to another care home. "He was thinking he'd get a room someplace in the Midwest, where you can see the sky and it's all clouds. 'Cause he loved that. It gave him such pleasure to see the grand spectacle of the sky. Something he never lost."

George died at 11:30 p.m. Sept. 6, his twin brother at his side. Mike called Jennifer Kroot, who came to the hospice with her husband and drove Mike home.

Kroot remembers, "The first thing Mike said was 'Well, I walked him to the gate.' "

Edward Guthmann is a Bay Area freelance writer. E-mail: datebookletters@sfchronicle.com